Notifications

We use cookies to personalise site content, social media features and to analyse our traffic. We also share information about your use of this site with our advertising and social media partners.

11 minutes, 23 seconds

-1.4K Views 0 Comments 0 Likes 0 Reviews

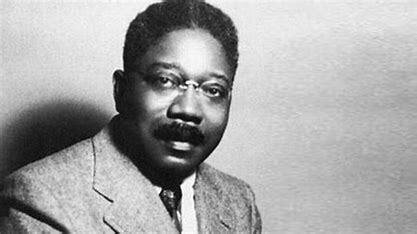

During the Harlem Renaissance—a time when African American artists, writers, and musicians were redefining Black identity—one man used brushstrokes instead of pen or piano keys. His name was Aaron Douglas, and he became the visual voice of a movement. Often called the “Father of African American Art,” Douglas created iconic imagery that blended African heritage with modern aesthetics, reshaping how Black Americans saw themselves and how the world saw them.

His signature style—characterized by bold silhouettes, rhythmic patterns, and spiritual overtones—graced everything from murals and magazine covers to books and academic halls. But more than decoration, his art was a declaration: that Black life, Black struggle, and Black brilliance belonged on the walls of history.

This blog explores the life, legacy, and enduring impact of Aaron Douglas—the man who turned paint into power.

Aaron Douglas was born on May 26, 1899, in Topeka, Kansas. Raised in a middle-class family, Douglas grew up in a supportive household where education and the arts were encouraged. His mother loved drawing and often passed down her passion for sketching to young Aaron.

After graduating high school, Douglas attended the University of Nebraska, where he earned a degree in Fine Arts in 1922. Like many young Black men of his time, Douglas initially took work as a high school art teacher. But he had a bigger dream: to become an artist who told the story of his people.

That dream led him to New York City in 1925, just as the Harlem Renaissance was in full bloom.

When Douglas arrived in Harlem, he was quickly embraced by a vibrant community of Black intellectuals, creatives, and activists. He studied with Winold Reiss, a German-born artist who encouraged Douglas to draw from African art, Egyptian imagery, and African American folk culture.

This mentorship helped Douglas develop his signature style: bold geometric shapes, stylized figures, sunbursts, and layered planes of color. His work was both modern and deeply rooted in African traditions—a perfect visual parallel to what writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston were doing in literature.

Douglas began contributing illustrations to The Crisis (the NAACP magazine edited by W.E.B. Du Bois) and Opportunity (published by the National Urban League). These publications gave him a platform to reach a national Black audience—and his art stood out immediately.

What made Aaron Douglas so pivotal was that he translated the goals of the Harlem Renaissance into visual form. While poets wrote about Black pride and jazz musicians played the rhythm of change, Douglas painted it.

He believed that art could uplift the race and educate the masses. In a time when Black people were portrayed through racist caricatures in mainstream media, Douglas offered an alternative: noble, dynamic, and spiritual depictions of Black life, past and present.

His illustrations featured powerful silhouettes in action—reading, marching, laboring, reaching for the stars. By stripping away facial details and emphasizing movement and symbolism, Douglas created universal Black figures that all African Americans could see themselves in.

Aaron Douglas’s most celebrated body of work is a series of murals titled “Aspects of Negro Life” (1934), commissioned by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for the New York Public Library’s 135th Street branch, now part of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

The four-panel series includes:

“The Negro in an African Setting” – Depicts African spiritual life and cultural roots, with tribal dances and ancestral worship.

“Slavery Through Reconstruction” – Shows the horrors of slavery, followed by emancipation and the rise of Black education.

“The Idyll of the Deep South” – Reflects post-emancipation hardship and the persistent presence of racial terror.

“From Slavery Through Reconstruction” – Charts a hopeful arc from bondage to progress, symbolized by upward-reaching figures and radiating light.

These murals told a sweeping narrative of the Black experience—from African origins to American transformation—with symbolism that continues to inspire and educate.

Another major commission came from Fisk University, where Douglas created a series of murals for the university library, illustrating Black contributions to culture, science, and world history. These works helped solidify his reputation as not only an artist but a historian and teacher through visual language.

Douglas’s art combined African motifs, cubist abstraction, and Art Deco elements, creating a style that was ahead of its time. Key themes in his work included:

Heritage and Ancestry: He often incorporated African masks, tribal patterns, and spiritual symbolism to remind African Americans of their noble origins.

Education and Enlightenment: Rays of light, books, and upward movement symbolized the pursuit of knowledge and progress.

Social Justice and Liberation: Douglas addressed slavery, segregation, and the ongoing struggle for equality with visual metaphors and heroic figures.

Unity and Identity: His work rejected individualism in favor of a collective Black identity—a visual call for solidarity.

His compositions were layered, literally and figuratively, blending the past, present, and future into unified narratives that challenged viewers to think, remember, and dream.

Aaron Douglas wasn’t just a painter—he was a pioneer. He helped define what African American visual art could be. Before him, Black art was often confined to portraits or traditional realism. Douglas broke free from those limitations, proving that Black stories could be told in modern, abstract, and radical ways.

He became a mentor to future generations of artists, and his work laid the foundation for Black art movements of the 1960s and beyond. His influence is visible in the works of artists like Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, and Kerry James Marshall.

Douglas also played a vital role in developing Black art institutions, helping to build platforms for emerging Black artists to showcase their work. He insisted that African American artists deserved recognition—not just in segregated venues, but in mainstream museums and universities.

In 1939, Aaron Douglas returned to academia, joining the faculty of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, a historically Black university. He taught there for nearly 30 years and established the Art Department, mentoring a new generation of Black artists and scholars.

Though he spent much of his later life in teaching, Douglas never stopped creating. His final years were quieter, but his influence only grew. He was honored in retrospectives and exhibitions, recognized as a giant in both the art world and the struggle for Black empowerment.

Douglas passed away in 1979, but his work remains as powerful today as it was nearly a century ago.

Today, Aaron Douglas is celebrated as a foundational figure in American art history. His murals are studied in universities, and his prints hang in major museums including the Smithsonian, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Schomburg Center.

His life’s work continues to resonate for its unapologetic celebration of Black culture and its challenge to injustice. In an era when the fight for racial equality remains urgent, Douglas’s art is not a relic—it’s a roadmap.

His pioneering style inspired not only visual artists but also poets, musicians, and filmmakers. Modern creators from Spike Lee to Kehinde Wiley cite Douglas as a source of inspiration.

Aaron Douglas didn’t just illustrate history—he reclaimed it, reimagined it, and restored dignity to a people too often left out of the picture. With every brushstroke, he told a deeper truth: that African Americans have always been central to the story of civilization, culture, and progress.

His art is a visual anthem of freedom—a song sung in shapes and shadows, in sunbursts and silhouettes. Through his vision, we see not only where we've been, but where we’re going.

As we look at his work today, we are reminded that art is more than beauty—it is a weapon, a teacher, a mirror, and a beacon.

And through Aaron Douglas, Black America found a master painter of its soul.

At our community we believe in the power of connections. Our platform is more than just a social networking site; it's a vibrant community where individuals from diverse backgrounds come together to share, connect, and thrive.

We are dedicated to fostering creativity, building strong communities, and raising awareness on a global scale.

Share this page with your family and friends.