Notifications

We use cookies to personalise site content, social media features and to analyse our traffic. We also share information about your use of this site with our advertising and social media partners.

12 minutes, 36 seconds

-1.4K Views 0 Comments 0 Likes 0 Reviews

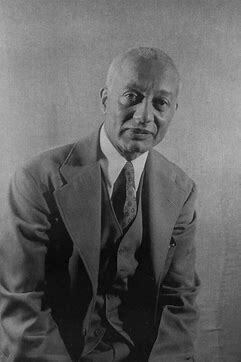

Alain LeRoy Locke may not have been the most flamboyant figure of the Harlem Renaissance, but he was undoubtedly one of its most essential minds. Known as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance” and the philosophical force behind the “New Negro” movement, Locke was an educator, philosopher, and cultural theorist whose ideas sparked one of the most influential periods of Black artistic and intellectual expression in American history.

Locke believed that art could be a powerful tool for social transformation. He championed Black artists, writers, and thinkers, urging them to break free from the stereotypes imposed by mainstream society and to redefine themselves on their own terms. His 1925 anthology, The New Negro: An Interpretation, became a landmark in African American literature and cultural history.

This blog explores the life, vision, and enduring impact of Alain Locke—a man whose ideas shaped a generation and whose legacy continues to inspire today.

Alain Locke was born on September 13, 1885, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a middle-class African American family. His father, Pliny Locke, was a lawyer and post office clerk, and his mother, Mary Hawkins Locke, was a schoolteacher. From an early age, Locke was steeped in a culture of education, discipline, and high expectations.

He excelled academically and became the first African American Rhodes Scholar in 1907, an achievement that broke racial barriers and drew national attention. He attended Harvard University, where he studied philosophy and earned his bachelor’s degree before heading to Oxford University for further studies. He later received a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard in 1918, making him one of the most highly educated African Americans of his time.

Despite his academic accolades, Locke faced deep racism in both the U.S. and Europe. At Oxford, he was excluded from many social circles because of his race. These experiences helped shape his commitment to using education and culture as tools for racial uplift and transformation.

By the early 1920s, Locke had become a respected professor at Howard University, a historically Black institution in Washington, D.C. But it was his work beyond the classroom that truly changed history.

In 1925, Locke edited and published the groundbreaking anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation. The book featured poetry, fiction, essays, and artwork by a wide range of Black voices, including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Countee Cullen.

The New Negro was more than just a collection—it was a manifesto. In its pages, Locke introduced the idea of the “New Negro”—a confident, self-respecting, and culturally aware African American who rejected passivity and demanded recognition as an equal participant in American life.

Locke wrote in the anthology’s introduction:

“The day of ‘aunties,’ ‘uncles,’ and ‘mammies’ is equally gone. Gone, too, is the full tide of sentimental appeal... The younger generation is vibrant with a new psychology; the new spirit is awake in the masses.”

This powerful framing helped spark a cultural revolution and established Locke as the intellectual father of the Harlem Renaissance.

The Harlem Renaissance, which flourished during the 1920s and early 1930s, was a vibrant movement of African American cultural and artistic expression centered in Harlem, New York. It was an era of jazz, poetry, novels, theater, and visual art—a reimagining of Black identity and creativity.

While many artists fueled the movement with their work, it was Locke who helped shape its philosophical direction. He argued that African American artists should embrace their cultural heritage—not only as Americans but as people of African descent. By drawing from African history, folk traditions, and the Black experience in America, artists could forge a new, empowered identity.

Locke believed that art could humanize the race in the eyes of white America while simultaneously fostering pride within the Black community. He saw cultural production not only as personal expression but as political action.

However, Locke’s vision wasn’t without controversy. Some criticized him for focusing more on aesthetic excellence and less on social critique. Writers like Langston Hughes and Richard Wright later expressed frustration with what they saw as Locke’s preference for art that appealed to white patrons and elite audiences.

Still, there’s no denying that Locke’s framework provided a powerful foundation for generations of Black artists and thinkers.

Locke was deeply influenced by philosophy—especially pragmatism, pluralism, and cultural relativism. He believed that no single culture held a monopoly on truth or beauty and that cross-cultural exchange was essential for societal progress.

His philosophical writings emphasized the importance of cultural pluralism, a belief that diverse cultures should coexist and enrich one another rather than assimilate into a dominant narrative. This view made Locke a natural supporter of Pan-Africanism, the movement advocating for solidarity among people of African descent worldwide.

He corresponded with and supported the work of W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and other leaders who believed in the global unification of African peoples, though he often maintained a more moderate and academic tone in his activism.

In Locke’s mind, the struggle for Black liberation was not just political—it was also cultural and spiritual. By reclaiming their cultural voice, African Americans could affirm their humanity and reshape their future.

Though Locke was a public intellectual, he was also a deeply private individual. He was known for his impeccable dress, aristocratic mannerisms, and love of classical music and the fine arts. As a gay Black man in early 20th-century America, Locke navigated multiple layers of identity with discretion and quiet resilience.

While he never spoke publicly about his sexuality, many biographers and scholars have acknowledged that Locke was likely gay and that this may have influenced his understanding of double marginalization—the feeling of being excluded on multiple fronts. This sensitivity may have deepened his commitment to elevating marginalized voices and championing diversity in all its forms.

Locke mentored and influenced a generation of Black writers and scholars, even when his relationships were sometimes strained. His correspondence with Langston Hughes, for example, reveals a complex mix of admiration, critique, and occasional conflict.

He continued teaching at Howard University for decades, despite frequent clashes with university administrators over academic freedom and curriculum design. He was a tireless advocate for Black studies and played a critical role in developing one of the first African American philosophy departments in the country.

Alain Locke passed away on June 9, 1954, in New York City. At the time of his death, much of his influence had faded from public memory. The Civil Rights Movement was on the horizon, and the Harlem Renaissance was seen by some as a nostalgic chapter in Black cultural history.

But Locke’s legacy would not remain dormant for long. In the decades that followed, historians, artists, and scholars began to reclaim his work and recognize his central role in shaping Black intellectual and cultural life.

His influence was reignited with the publication of biographies like Jeffrey C. Stewart’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke (2018), which brought renewed attention to Locke’s complexity and brilliance. Stewart’s book portrayed Locke not just as a cultural curator but as a radical visionary who laid the groundwork for Black pride movements long before the term “Black Power” was coined.

Today, Alain Locke is remembered as one of the founders of Black modern thought. His ideas remain foundational in African American studies, cultural theory, and the philosophy of race.

His influence can be seen in:

The rise of Black Arts Movements in the 1960s and beyond

The development of Black Studies and African American literature curricula in universities

The continuing debate over the role of art in social change

The cultural pride movements that have empowered artists and activists of color across generations

In 2007, Locke’s remains were reinterred at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., beneath a tombstone inscribed with:

"Herald of the Harlem Renaissance."

A fitting tribute for a man who helped awaken a generation’s voice.

Alain Locke was a thinker ahead of his time. In an era when Black Americans were fighting to be seen and heard, he urged them to create, express, and define themselves through art and intellect. He believed that Black culture was not a subset of American culture—it was an essential part of it, deserving of respect, study, and celebration.

Through his vision of the New Negro, Locke challenged the world to see African Americans not as caricatures, victims, or novelties—but as creators, innovators, and full participants in the human experience.

In a society still grappling with questions of race, identity, and justice, Alain Locke’s voice remains as relevant today as it was nearly a century ago.

At our community we believe in the power of connections. Our platform is more than just a social networking site; it's a vibrant community where individuals from diverse backgrounds come together to share, connect, and thrive.

We are dedicated to fostering creativity, building strong communities, and raising awareness on a global scale.

Share this page with your family and friends.