Notifications

We use cookies to personalise site content, social media features and to analyse our traffic. We also share information about your use of this site with our advertising and social media partners.

12 minutes, 32 seconds

-1K Views 0 Comments 0 Likes 0 Reviews

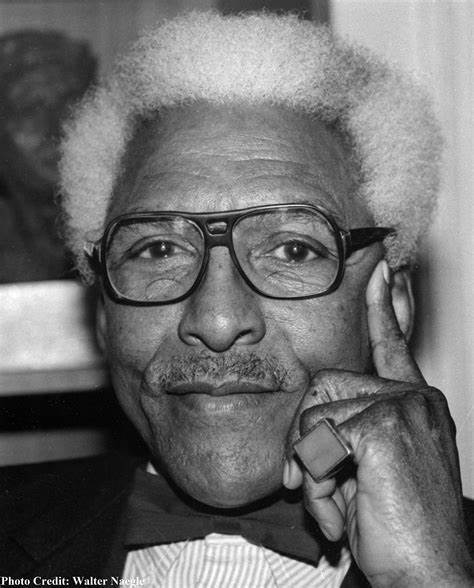

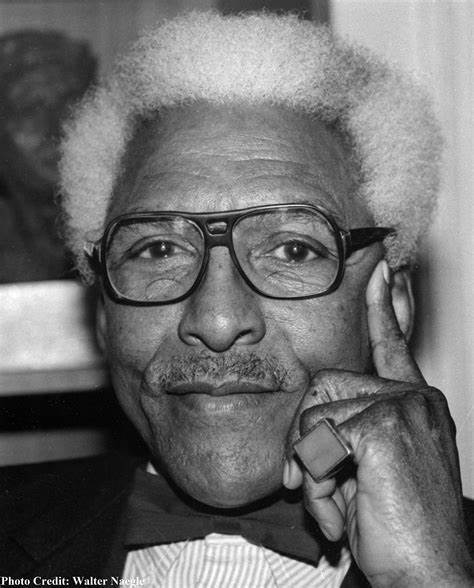

Bayard Rustin was one of the most brilliant minds and strategic organizers of the American civil rights movement. Yet, his name is often left out of history books and public commemoration. A key advisor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the chief architect of the 1963 March on Washington, and a lifelong advocate for nonviolence, socialism, and human rights, Rustin’s contributions were immense. However, because he was a gay man in an era of rampant homophobia, his leadership was often pushed into the background.

Today, as conversations about intersectionality, inclusion, and the diversity of leadership grow louder, it is long past time to give Bayard Rustin the recognition he deserves—not only as a tactician of justice, but as a moral visionary whose life offers powerful lessons for our current generation.

Bayard Taylor Rustin was born on March 17, 1912, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and raised by his maternal grandparents, who were devout Quakers. His grandmother, Julia Davis Rustin, had a profound influence on his moral and political worldview. She instilled in him the Quaker belief in the inner light of every human being and the importance of peace, integrity, and justice.

From an early age, Rustin exhibited a remarkable intellect and a strong sense of personal ethics. He also faced the challenges of growing up Black and gay in early 20th-century America. Despite those barriers, he attended Wilberforce University, Cheyney State Teachers College, and later studied at the City College of New York, where he was exposed to a wide range of radical political ideas, including socialism, labor rights, and anti-colonialism.

Rustin’s early activism included protesting against segregation in the military and public transportation systems. In 1941, he joined A. Philip Randolph in planning the first proposed March on Washington to protest racial discrimination in the defense industry—a march that was only called off after President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, banning such discrimination in federal defense contracts.

Rustin was deeply influenced by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and became a dedicated pacifist. During World War II, he refused military service as a conscientious objector, which led to his imprisonment for over two years. While incarcerated, he continued to organize for racial equality and prisoners’ rights.

After the war, Rustin became involved with the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and later co-founded the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). He helped plan the 1947 "Journey of Reconciliation," a precursor to the Freedom Rides of the 1960s. The campaign tested the Supreme Court’s ruling that banned segregation in interstate bus travel, and it led to Rustin’s arrest and a brutal 22-day chain gang sentence in North Carolina.

Despite these personal hardships, Rustin never wavered in his commitment to nonviolence and direct action. He viewed the struggle for justice as a spiritual and moral calling, one that required discipline, sacrifice, and a deep commitment to the principles of love and truth.

In the mid-1950s, Rustin traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, to advise a young Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Rustin brought with him a wealth of experience in nonviolent resistance and helped King fully embrace the philosophy of Gandhian nonviolence, not just as a tactic, but as a way of life.

He also helped draft organizing manuals and trained King’s staff in the methods of civil disobedience and mass mobilization. Though immensely valuable behind the scenes, Rustin's visibility was often limited due to concerns about his homosexuality and past ties to socialist organizations.

Some leaders in the movement feared that his presence would be used by opponents to discredit the movement. Still, Rustin continued to advise King and other civil rights leaders, knowing that the struggle was bigger than any one individual’s ego or public recognition.

Bayard Rustin’s most visible and historic contribution came in 1963 when he was selected to serve as the chief organizer of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The event became one of the most iconic moments in American history, remembered for Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and the unity of over 250,000 people peacefully demanding civil rights, economic justice, and racial equality.

Organizing such a massive event required meticulous planning, coalition-building, logistics, and coordination with national labor unions, religious groups, student organizations, and civil rights associations. Rustin worked tirelessly, often sleeping only a few hours a night, managing every detail from transportation to security.

Despite attempts by politicians and even some civil rights leaders to keep him in the background, Rustin stood on the stage during the event—though not as a keynote speaker. The March’s success was a testament to his brilliance and strategic discipline. It demonstrated that mass movements could be peaceful, unified, and effective—and it shifted the national conscience.

After the March on Washington, Rustin’s involvement in civil rights continued, though his role became increasingly shaped by his broader international vision. He became involved with Social Democrats USA and began focusing on labor rights, anti-poverty initiatives, and democratic socialism.

Rustin believed deeply in coalition politics—the idea that social progress could be achieved through broad-based alliances across race, class, and ideology. This sometimes put him at odds with the Black Power movement in the late 1960s, which favored a more militant and separatist approach. Rustin, always a believer in integration and universal human rights, argued that real progress required inclusion and working within democratic institutions.

He also became a vocal advocate for global human rights, supporting independence movements in Africa, speaking out against apartheid in South Africa, and defending dissidents in the Soviet Union. Rustin's activism increasingly turned to issues of international peace, economic development, and civil liberties on a global scale.

Rustin’s identity as a gay man was both a source of vulnerability and strength. He was arrested in 1953 for homosexual activity, a charge that was often used to discredit him politically. Throughout his life, he was advised to hide his sexuality to avoid controversy. Though he never made his sexual orientation a central issue, he lived with dignity and integrity, refusing to apologize for who he was.

In the 1980s, as the LGBTQ+ rights movement gained momentum, Rustin began speaking more openly about the connections between homophobia and other forms of oppression. In one of his final essays, he wrote:

"Today, blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change. Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new ‘barometer’ of social change is the treatment of gay and lesbian people."

This recognition of intersectionality—that the fight for civil rights must include all marginalized people—was a powerful message, especially from someone who had long been asked to remain silent about his identity.

Bayard Rustin passed away on August 24, 1987, from a ruptured appendix. Though he died without the recognition given to many of his peers, history has begun to acknowledge his extraordinary contributions.

In 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. In 2020, the Netflix film Rustin, produced by the Obamas’ production company, further amplified his legacy to a new generation. Streets, schools, and social justice centers have since been named in his honor.

But perhaps Rustin’s most important legacy lies in his methodology. He taught that movements must be strategic as well as moral, that leadership can come from the margins, and that true justice includes everyone, regardless of race, class, or sexual orientation.

Bayard Rustin was a visionary whose life defied conventional labels. He was a Black man, a gay man, a pacifist, a socialist, a Christian, a global thinker, and an unapologetic dreamer. Though history once tried to silence him, his voice echoes louder than ever in today’s movements for justice and equality.

He organized not for personal glory, but to lift others. He believed that love was not just a feeling, but a political act. And he understood that real progress is never easy—it takes years of planning, sacrifice, and the courage to stand alone when necessary.

Rustin showed us that you don’t have to be in the spotlight to change the world. You just have to stand in your truth, work relentlessly, and never lose faith in the power of collective action. His life reminds us that the road to justice is long, but every step—every march, every meeting, every quiet act of resistance—brings us closer to the world we believe in.

At our community we believe in the power of connections. Our platform is more than just a social networking site; it's a vibrant community where individuals from diverse backgrounds come together to share, connect, and thrive.

We are dedicated to fostering creativity, building strong communities, and raising awareness on a global scale.

Share this page with your family and friends.