Introduction

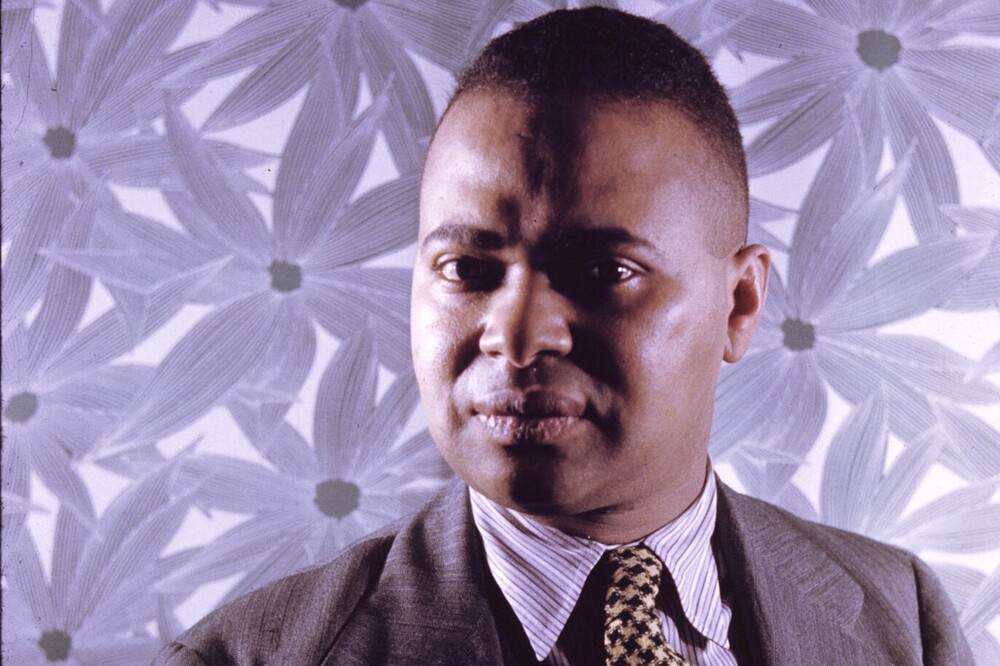

In the symphony of voices that defined the Harlem Renaissance, Countee Cullen stood out as the refined, lyrical poet who brought classical grace to the vibrant spirit of Black cultural awakening. With formal technique, emotional depth, and powerful themes of race, identity, and love, Cullen bridged two worlds: the traditional poetics of European literature and the new wave of African American expression emerging in 1920s Harlem.

Though he lived a relatively short life, Cullen's impact on American literature was immense. He became one of the leading voices of the Harlem Renaissance, earning acclaim for his ability to elevate the Black experience through verse without abandoning the classical forms he revered. Through his work, Cullen demonstrated that Black poets could not only match but master the literary traditions of the Western canon—while still asserting their unique cultural identity.

This blog explores the life, works, and legacy of Countee Cullen—poet, teacher, and quiet revolutionary.

Early Life and Education

Countee Cullen was born on May 30, 1903, though the exact date and location remain uncertain due to conflicting records. Some sources suggest he was born in Louisville, Kentucky, or Baltimore, Maryland, but he was raised primarily in New York City. After the death of his parents (or in some accounts, being orphaned at a young age), he was adopted or informally taken in by the Reverend Frederick A. Cullen, a prominent African American minister and the pastor of Salem Methodist Episcopal Church in Harlem.

Reverend Cullen was a well-connected figure in New York’s Black community and gave Countee access to an elite education. Cullen attended DeWitt Clinton High School, where he quickly gained a reputation for his literary talent, winning several poetry contests and publishing in school magazines.

He continued his studies at New York University (NYU), where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1925, and later earned a master’s degree in English and French from Harvard University. His academic background, steeped in classical literature, would deeply inform his poetic style.

A Classical Poet in a Modern Movement

What distinguished Cullen from many of his Harlem Renaissance peers was his commitment to traditional poetic forms. While writers like Langston Hughes and Claude McKay embraced jazz rhythms, African American vernacular, and free verse, Cullen favored sonnets, rhymed couplets, and metaphysical allusions.

He idolized poets like John Keats, William Wordsworth, and A.E. Housman, and believed that African American poets should be judged by the same standards as their white counterparts. This position sometimes put him at odds with other writers of the Renaissance, who wanted to establish a distinctly Black literary voice free from European influence.

In his 1927 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Langston Hughes criticized Black artists who aspired to be “white,” accusing them of rejecting their cultural roots. Many interpreted this as a critique of Cullen, though Cullen never disavowed his racial identity. He simply believed that the universal themes of beauty, love, and pain transcended race—and that Black writers should be free to explore them in the language and forms they chose.

Breakthrough with Color

Cullen’s debut poetry collection, Color (1925), was a watershed moment in African American literature. Published the same year he graduated from NYU, the collection received widespread acclaim and established Cullen as a rising star.

The poems in Color grappled with Cullen’s dual identity: as a Black man in a racially oppressive society and as a classically trained poet yearning for universal beauty. The title itself signaled the theme that would define much of his work: the tension between racial identity and artistic universality.

The collection includes one of his most famous poems, “Incident,” a brief but devastating memory from his childhood:

Once riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee;

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me...

Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me, “Nigger.”

I saw the whole of Baltimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That's all that I remember.

The poem’s simplicity and stark emotional impact made it one of the most anthologized poems of the 20th century. In just 12 lines, Cullen captured the psychological scars of racism and the loss of childhood innocence.

Other notable poems from Color include “Heritage,” a meditation on his African ancestry and his place in modern America, and “Yet Do I Marvel,” a sonnet questioning the inscrutability of divine justice in the face of Black suffering.

Themes in Cullen’s Work

Cullen’s poetry, while grounded in classical form, explored deeply personal and socially relevant themes:

-

Race and Racism: He frequently addressed the pain and injustice of racial discrimination, though often with subtlety and restraint.

-

Religion and God: A recurring theme in his work is the tension between Christian teachings and the realities of Black life. He often questioned God’s purpose in allowing suffering.

-

Identity and Duality: Cullen struggled with being a Black artist in a white literary world and often explored this inner conflict.

-

Love and Beauty: Like the Romantics he admired, Cullen celebrated beauty and emotional longing, including themes that hinted at homoerotic desire—a subject rarely addressed openly in his era.

Personal Life and Challenges

Cullen’s personal life was as complex as his poetry. In 1928, he married Yolande Du Bois, the daughter of the famous scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, in what was called the social event of the decade among the Black elite. Langston Hughes served as a groomsman, and hundreds of guests attended.

However, the marriage was short-lived. It ended in divorce two years later, and many scholars believe the union was troubled by Cullen’s sexual orientation—a topic that was taboo at the time but has since become a key element in understanding his inner world. His letters and poetry suggest he had romantic feelings for men, and his work contains subtle expressions of same-sex desire cloaked in metaphor and ambiguity.

Later in life, Cullen found more personal stability and married Ida Mae Robertson in 1940, with whom he remained until his death.

A Life in Education

In addition to his literary pursuits, Cullen was deeply committed to education. He spent most of his later years teaching English and French at Frederick Douglass Junior High School in Harlem. Among his students was a young James Baldwin, who would go on to become one of the most important voices in American literature and civil rights.

Cullen believed in nurturing talent and empowering the next generation through knowledge and discipline. Though his public profile diminished in the 1930s and 1940s, he continued to write and publish quietly while shaping minds in the classroom.

Later Works and Final Years

After the initial burst of fame in the 1920s, Cullen’s literary output slowed. Still, he remained an active cultural figure. He wrote children’s books, plays, and continued to publish poetry.

In 1946, Cullen published The Lost Zoo, a whimsical children’s book written in verse. He also worked with the American Negro Theatre and was involved in translating and adapting classical works for Black audiences.

Tragically, Countee Cullen died young—on January 9, 1946, at the age of 42, from high blood pressure and related complications. His death marked the end of a quiet but influential chapter in American letters.

Legacy and Impact

Countee Cullen's legacy is rich and enduring. Though overshadowed in popular memory by the more overtly political voices of the Harlem Renaissance, Cullen’s literary craftsmanship and introspective poetry remain vital to the understanding of Black modernism.

His influence is felt in:

-

The continued teaching and anthologizing of his poems in schools and universities.

-

The evolution of queer Black literature—where Cullen is now recognized as a complex figure navigating sexual and racial identity.

-

The tradition of Black poets who combine formal mastery with emotional depth, such as Natasha Trethewey, Terrance Hayes, and Jericho Brown.

In a time when Black voices were often expected to conform to specific narratives, Cullen insisted on artistic freedom and emotional honesty. His work proved that beauty and protest could coexist—and that a poem could be both timeless and timely.

Conclusion

Countee Cullen lived at the crossroads of tradition and transformation. He was a classical poet in a revolutionary age, a private soul in a public movement, and a Black man demanding space in a world that denied his worth.

Through elegant verse and quiet conviction, he helped redefine what it meant to be a Black artist in America. In doing so, he left behind a body of work that continues to speak—softly, beautifully, and powerfully—to the complexity of the human experience.

As Cullen once wrote in Yet Do I Marvel:

Yet do I marvel at this curious thing:

To make a poet Black, and bid him sing!

Sing he did—and the world is better for it.

Share this page with your family and friends.