Notifications

We use cookies to personalise site content, social media features and to analyse our traffic. We also share information about your use of this site with our advertising and social media partners.

11 minutes, 2 seconds

-1.1K Views 0 Comments 0 Likes 0 Reviews

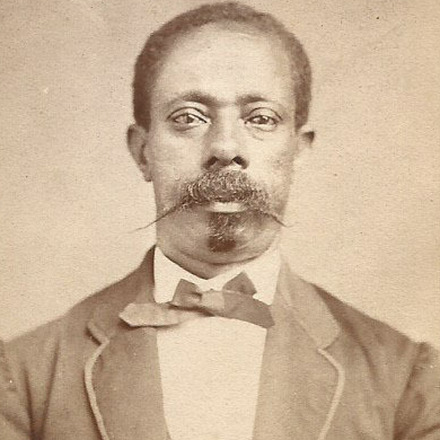

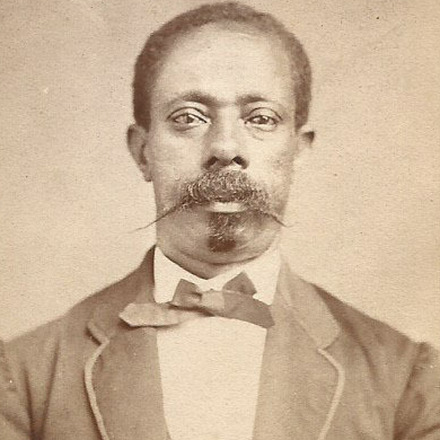

When people think of the abolitionist movement in America, names like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth often come to mind. Yet, before many of them rose to prominence, there was David Walker, a free Black man whose radical ideas and fiery rhetoric in the early 19th century shook both the North and South to their core.

Walker’s most famous work, David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, was more than just a pamphlet—it was a revolutionary call to action. Passionate, fearless, and grounded in both moral and political urgency, Walker’s words reverberated across the nation and changed the tone of the abolitionist movement forever.

David Walker was born in 1796 in Wilmington, North Carolina, to a free Black mother and an enslaved father. Because of his mother’s status, Walker was born free—a legal technicality that would profoundly shape his destiny.

Growing up in the American South, Walker witnessed firsthand the brutal realities of slavery. Though free, he lived in a society where African Americans—whether free or enslaved—were constantly dehumanized. Free Blacks like Walker were treated with suspicion, subjected to restrictive laws, and lived under constant threat.

His early experiences instilled in him a deep sense of injustice and lit a fire that would never go out.

In the early 1820s, Walker moved to Boston, a city with a more vibrant free Black community and a growing abolitionist presence. There, he opened a second-hand clothing store and quickly became an integral part of the Black intellectual and activist circles.

Boston gave Walker not only a platform but a purpose. He became active in church leadership, joined abolitionist groups, and began writing about the plight of Black Americans with increasing urgency. He was a contributor to the early Black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, and used every avenue available to speak out against slavery and racism.

But he wasn’t just any voice in the abolitionist choir—he was one of its most radical and uncompromising.

In 1829, David Walker published his groundbreaking pamphlet:

“Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America.”

The Appeal was unlike anything the American public had seen. It wasn’t polite. It wasn’t cautious. It wasn’t content with gradual change. It was blunt, incendiary, and unapologetically militant.

Walker addressed Black readers directly, urging them to rise up against their oppression—not just spiritually or morally, but physically if necessary.

The Hypocrisy of Christian Slaveholders: Walker condemned the use of Christianity to justify slavery, pointing out that the Bible preached love, justice, and freedom.

The Inhumanity of Slavery: He detailed the suffering of enslaved people with brutal honesty.

A Call to Resistance: Walker argued that enslaved people had the right to revolt and that it was unjust to ask them to wait for their freedom.

Racial Equality: He emphasized that Black people were not inferior and deserved full human rights, dignity, and liberty.

Walker wrote:

“America is more our country than it is the whites’ — we have enriched it with our blood and tears.”

He wasn’t simply begging for freedom—he was demanding it.

Walker’s pamphlet spread quickly—but not without resistance. Southern states reacted with immediate and intense fear. The Appeal was considered so dangerous that it was banned in many states, and simply possessing a copy could result in imprisonment—or worse.

Southern authorities accused Walker of trying to incite a slave rebellion. In fact, his pamphlet circulated just two years before Nat Turner's Rebellion in 1831, and many in the South blamed Walker for fueling such unrest.

Walker didn’t wait for mainstream publishers to spread his message. He used a grassroots method—hiding copies in clothing shipped from his Boston store to the South. This underground distribution mirrored the clandestine networks that would later define the Underground Railroad.

Walker was a deeply religious man. His understanding of justice was not just political but theological. He saw slavery as a sin against God, and he often quoted scripture in his arguments. Unlike some abolitionists who framed their arguments in terms of social progress or political necessity, Walker made a moral and divine case for ending slavery immediately.

In one powerful passage, he wrote:

“The Americans may have some little chance to repent of their sins and be saved, but if they do not... I fear their destruction.”

To Walker, America’s fate was intertwined with its treatment of Black people. Without repentance and justice, he believed the nation was headed for divine judgment.

Not everyone in the abolitionist community embraced Walker’s message. Many white and even some Black abolitionists of the time thought his tone was too militant and that his call for resistance could provoke violent backlash.

But Walker wasn’t concerned about offending sensibilities. He had seen too much suffering to be polite about injustice.

His boldness paved the way for later figures like Frederick Douglass, who initially favored a more diplomatic approach but later came to echo many of Walker’s ideas.

Just one year after the publication of his Appeal, David Walker died suddenly in 1830 at the age of 33 or 34. The exact cause of his death remains unclear, and many have speculated he may have been poisoned by those who saw him as a threat.

Though his life was cut short, his impact was lasting.

Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Malcolm X all acknowledged Walker’s influence.

His Appeal is considered one of the first major anti-slavery documents published by an African American.

Today, Walker is seen as a precursor to Black nationalism, civil rights activism, and the tradition of Black liberation theology.

He planted the seeds of radical resistance that would blossom in generations to come.

David Walker's message still echoes today. At a time when sanitized history often strips radical figures of their power, revisiting Walker’s Appeal is a reminder that true change often begins with uncomfortable truths.

Walker did not believe in waiting for the oppressor to find a conscience. He believed in the righteous rage of the oppressed, in self-determination, and in the urgency of justice.

In an era where racism continues to rear its head in various forms, from systemic inequality to overt violence, Walker’s words remain deeply relevant. He reminds us that freedom is not freely given—it must be demanded, fought for, and protected.

David Walker lived in a time when speaking out as a Black man could cost you your life. And yet, he did not whisper—he roared.

He confronted not only white supremacy but also the caution and hesitation within his own community. He challenged America to live up to its ideals and warned that failing to do so would lead to destruction.

In his own words:

“The man who would not fight… ought to be kept with the beasts of the forest.”

Walker believed in the strength, dignity, and destiny of Black people. He saw them not as victims but as revolutionaries in waiting.

David Walker was not just a writer or activist. He was a prophet of justice—and though he may not have lived to see the abolition of slavery, he helped light the fire that would one day burn it down.

At our community we believe in the power of connections. Our platform is more than just a social networking site; it's a vibrant community where individuals from diverse backgrounds come together to share, connect, and thrive.

We are dedicated to fostering creativity, building strong communities, and raising awareness on a global scale.

Share this page with your family and friends.